Post History

#2: Post edited

- First, there’s a couple of algebraic errors in your question:

- * $\sqrt{a} \sqrt{b} = \sqrt{ab}$ is only true for real numbers, not complex numbers or quaternions

- * $x^2 = y$ does **not** necessarily imply that $x = \sqrt{y}$

- Keep in mind that the radical sign $\surd$ means the *principal* root. Even when just dealing with real numbers, there are **two** solutions to (e.g.) $x^2 = 4$, and $\sqrt{4}$ denotes only one of them. (Which one this is, is a matter of convention rather than necessity.)

- Now, in contrast to [the perfectly reasonable answer](https://math.codidact.com/posts/285984/285986#answer-285986) by [whybecause](https://math.codidact.com/users/55022), I’m going to say that we *can*, in fact, treat quaternion-$i$ as imaginary-unit-$i$. I think this is helpful because it lets us use some of the ways of thinking about complex numbers to look at quaternions and see how they’re similar… and more importantly, how they’re different.

- Specifically, I’m quite fond of the geometric interpretation of multiplying by a complex number—that is, scaling by its magnitude and rotating by its argument. Since we’re dealing solely with unit-magnitude quantities, we can ignore the former and look purely at rotations. And if multiplying by a quantity is a rotation, then finding its square root means finding *half* of that rotation.

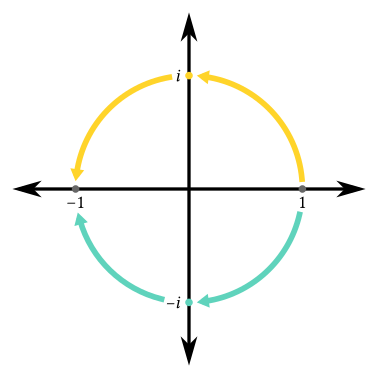

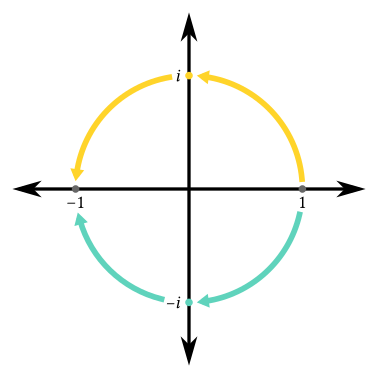

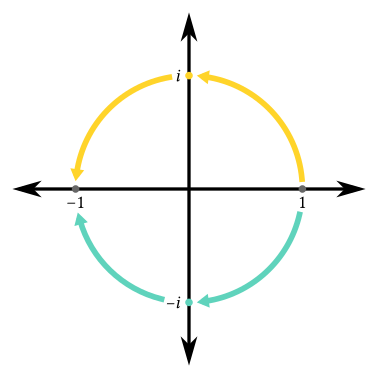

- In the one-dimensional real number line, there are no square roots of −1. In the two-dimensional complex number plane, there are two roots; we call them $i$ and $-i$ and designate the former as the principal root. There are two, because in the plane there are two ways to rotate by a half-turn (clockwise and anti-clockwise), and so there are two different ways to halve it:

-

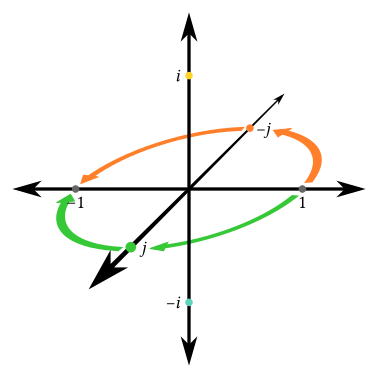

Now, if we move from the complex plane to a three-dimensional space, we add two more roots. We can call them $j$ and $-j$. We have two orthogonal axes of rotation, and we can do a quarter-turn around both, either clockwise or anti-clockwise:-

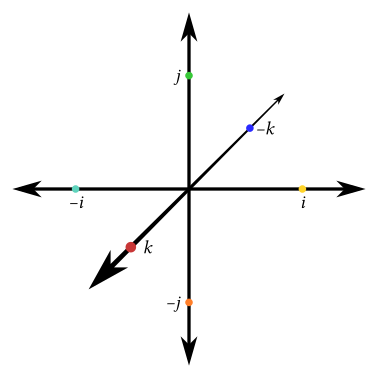

And if we add yet another dimension, we get the four-dimensional quaternion space. This adds *another* orthogonal axis of rotation, with both clockwise and anti-clockwise directions, so we have two more roots of −1. We can call these $k$ and $-k$.I’m not even going to try to draw this, by the way; there’s [a decent (albeit simple) drawing](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Quaternion_2.svg) on the Wikipedia page [“Quaternion”](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quaternion) if you want one. What I *will* draw is the three-dimensional space of the three non-real quaternion axes:-

- In this view, we can treat multiplication by each unit as a quarter-turn rotation about its own axis—a turn to the right, if your head is at the unit in question and your feet are at the origin.

- Finally, this also shows why quaternion multiplication is non-commutative. If you stand up along the $j$ axis (head at $j$, feet at origin), look at $i$, and rotate a quarter-turn to the right, you’re looking at $k$: $ij = k$. But if you lay along the $i$ axis (head at $i$, feet at origin), look at $j$, and rotate a quarter-turn to the right, now you’re looking at $-k$ instead: $ji = -k$.

- (As for why multiplications like $ii$ and $ijk$ take us back to real numbers, clearly it’s because you’re trying to look at your own head and then rotate it, at which point your brain implodes and you revert to elementary mathematics. 😉)

- First, there’s a couple of algebraic errors in your question:

- * $\sqrt{a} \sqrt{b} = \sqrt{ab}$ is only true for real numbers, not complex numbers or quaternions

- * $x^2 = y$ does **not** necessarily imply that $x = \sqrt{y}$

- Keep in mind that the radical sign $\surd$ means the *principal* root. Even when just dealing with real numbers, there are **two** solutions to (e.g.) $x^2 = 4$, and $\sqrt{4}$ denotes only one of them. (Which one this is, is a matter of convention rather than necessity.)

- Now, in contrast to [the perfectly reasonable answer](https://math.codidact.com/posts/285984/285986#answer-285986) by [whybecause](https://math.codidact.com/users/55022), I’m going to say that we *can*, in fact, treat quaternion-$i$ as imaginary-unit-$i$. I think this is helpful because it lets us use some of the ways of thinking about complex numbers to look at quaternions and see how they’re similar… and more importantly, how they’re different.

- Specifically, I’m quite fond of the geometric interpretation of multiplying by a complex number—that is, scaling by its magnitude and rotating by its argument. Since we’re dealing solely with unit-magnitude quantities, we can ignore the former and look purely at rotations. And if multiplying by a quantity is a rotation, then finding its square root means finding *half* of that rotation.

- In the one-dimensional real number line, there are no square roots of −1. In the two-dimensional complex number plane, there are two roots; we call them $i$ and $-i$ and designate the former as the principal root. There are two, because in the plane there are two ways to rotate by a half-turn (clockwise and anti-clockwise), and so there are two different ways to halve it:

-

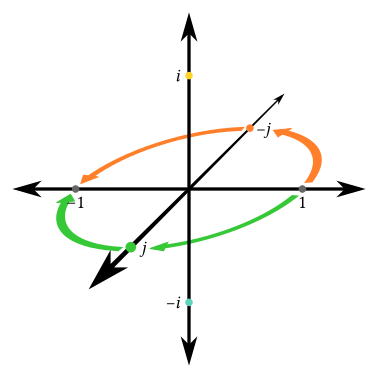

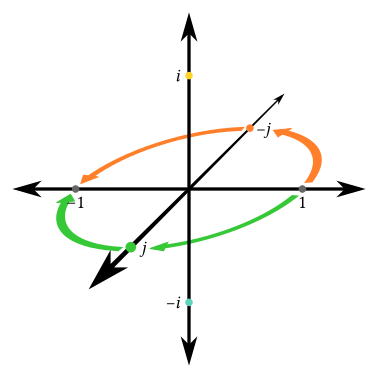

- Now, if we move from the complex plane to a three-dimensional space, we add two more roots. We can call them $j$ and $-j$. We have two orthogonal planes we can rotate through, and we can do a quarter-turn in either, going either clockwise or anti-clockwise:

-

- And if we add yet another dimension, we get the four-dimensional quaternion space. This adds *another* orthogonal plane to rotate in, with both clockwise and anti-clockwise directions, so we have two more roots of −1. We can call these $k$ and $-k$.

- *(Note: Originally I described the rotations as being about axes, not in planes. In 3D, these are equivalent, because any given plane has just one perpendicular axis through the origin. In 4D, this is no longer true!)*

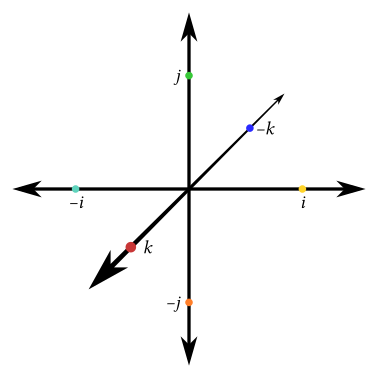

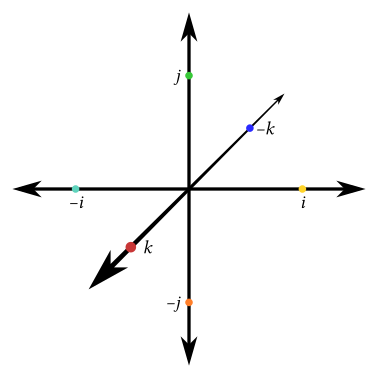

- I’m not even going to try to draw this four-dimensional space, by the way; there’s [a decent (albeit simple) drawing](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Quaternion_2.svg) on the Wikipedia page [“Quaternion”](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quaternion) if you want one. What I *will* draw is the three-dimensional space of the three non-real quaternion axes:

-

- In this view, we can treat multiplication by each unit as a quarter-turn rotation about its own axis—a turn to the right, if your head is at the unit in question and your feet are at the origin.

- Finally, this also shows why quaternion multiplication is non-commutative. If you stand up along the $j$ axis (head at $j$, feet at origin), look at $i$, and rotate a quarter-turn to the right, you’re looking at $k$: $ij = k$. But if you lay along the $i$ axis (head at $i$, feet at origin), look at $j$, and rotate a quarter-turn to the right, now you’re looking at $-k$ instead: $ji = -k$.

- (As for why multiplications like $ii$ and $ijk$ take us back to real numbers, clearly it’s because you’re trying to look at your own head and then rotate it, at which point your brain implodes and you revert to elementary mathematics. 😉)

#1: Initial revision

First, there’s a couple of algebraic errors in your question:

* $\sqrt{a} \sqrt{b} = \sqrt{ab}$ is only true for real numbers, not complex numbers or quaternions

* $x^2 = y$ does **not** necessarily imply that $x = \sqrt{y}$

Keep in mind that the radical sign $\surd$ means the *principal* root. Even when just dealing with real numbers, there are **two** solutions to (e.g.) $x^2 = 4$, and $\sqrt{4}$ denotes only one of them. (Which one this is, is a matter of convention rather than necessity.)

Now, in contrast to [the perfectly reasonable answer](https://math.codidact.com/posts/285984/285986#answer-285986) by [whybecause](https://math.codidact.com/users/55022), I’m going to say that we *can*, in fact, treat quaternion-$i$ as imaginary-unit-$i$. I think this is helpful because it lets us use some of the ways of thinking about complex numbers to look at quaternions and see how they’re similar… and more importantly, how they’re different.

Specifically, I’m quite fond of the geometric interpretation of multiplying by a complex number—that is, scaling by its magnitude and rotating by its argument. Since we’re dealing solely with unit-magnitude quantities, we can ignore the former and look purely at rotations. And if multiplying by a quantity is a rotation, then finding its square root means finding *half* of that rotation.

In the one-dimensional real number line, there are no square roots of −1. In the two-dimensional complex number plane, there are two roots; we call them $i$ and $-i$ and designate the former as the principal root. There are two, because in the plane there are two ways to rotate by a half-turn (clockwise and anti-clockwise), and so there are two different ways to halve it:

Now, if we move from the complex plane to a three-dimensional space, we add two more roots. We can call them $j$ and $-j$. We have two orthogonal axes of rotation, and we can do a quarter-turn around both, either clockwise or anti-clockwise:

And if we add yet another dimension, we get the four-dimensional quaternion space. This adds *another* orthogonal axis of rotation, with both clockwise and anti-clockwise directions, so we have two more roots of −1. We can call these $k$ and $-k$.

I’m not even going to try to draw this, by the way; there’s [a decent (albeit simple) drawing](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Quaternion_2.svg) on the Wikipedia page [“Quaternion”](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quaternion) if you want one. What I *will* draw is the three-dimensional space of the three non-real quaternion axes:

In this view, we can treat multiplication by each unit as a quarter-turn rotation about its own axis—a turn to the right, if your head is at the unit in question and your feet are at the origin.

Finally, this also shows why quaternion multiplication is non-commutative. If you stand up along the $j$ axis (head at $j$, feet at origin), look at $i$, and rotate a quarter-turn to the right, you’re looking at $k$: $ij = k$. But if you lay along the $i$ axis (head at $i$, feet at origin), look at $j$, and rotate a quarter-turn to the right, now you’re looking at $-k$ instead: $ji = -k$.

(As for why multiplications like $ii$ and $ijk$ take us back to real numbers, clearly it’s because you’re trying to look at your own head and then rotate it, at which point your brain implodes and you revert to elementary mathematics. 😉)